“I believe that Warhol, his works, his figure, are very important and actual for us all because, as you know, what you can’t get away from you must learn to love. It is the only way out. Warhol is an excellent teacher in this, since he did come to love the inevitable presence of mass images.”

Pavel Pepperstein, commenting on Sots Art,the starting point for the Russian version of Pop Art.

I am not a regular visitor to the Saatchi Gallery. On the rare occasions when I have been before I have been disappointed by the shallowness of what was on offer. So when I was walking past and decided to go in for a visit it was with low expectations. I left some 90 minutes later having enjoyed myself more than I could possibly have imagined.

The current exhibition at the gallery is Post Pop: East meets West, a large, gaudy and vulgar exhibition of Pop Art from the last forty years, drawn from the UK, US and, most importantly, Russia and China. The exhibition fills the entire gallery and includes work by well known names like Rachel Whiteread. And as with any large exhibition there is stuff to admire and stuff to ignore. It doesn’t all work. I found much of the American and British work in the exhibition to be uninspiring. The Chinese work was interesting, but it was hard to discern a common theme. The most interesting work in the exhibition is the large number of Russian works as they collectively tell an important and interesting story about that country.

Pop Art originated in the 1950s and 60s with artists like Blake, Hamilton, Lichtenstein and Warhol. The essence of Pop Art is the appropriation of images from other sources and their subsequent subversion through the use of visual parody and irony. In its original form the source images were normally drawn from icons of modern consumer culture and society, though they could equally well be drawn from art itself or from other parts of the media, and the resulting subverted images were a commentary on popular culture, mass production and an explicit criticism of the tendency to think of art as elitist or difficult. The term Post Pop seems to have been chosen by the curators to narrow their focus to the next generations of artists who followed on from the original Pop Art pioneers.

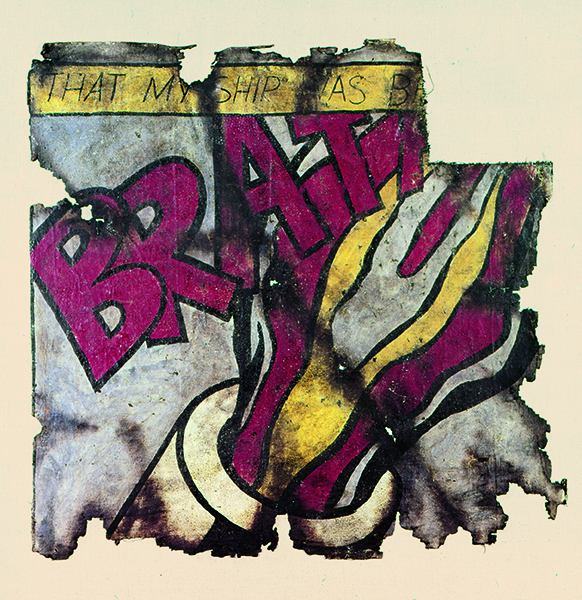

In a fascinating introductory essay, Andrei Erofeev traces the development of Soviet Post Pop Art, normally called Sots Art, to the early work of Komar and Melamid in 1974. In a complex assemblage of ‘found’ materials they imagined archaeologists recovering fragments of a lost work before the Third World War. Amongst the fragments were charred remains of famous Pop Art paintings.

Presented as one of a few found fragments of art from before a nuclear apocalypse. Also found were notebooks documenting Soviet soldiers entering London and Washington and engravings of Romantic ruins featuring JFK Airport amongst other locations.

It is hard for us to conceive now the level of isolation from international developments in art that Russian artists had to accept as their reality at that stage. In Stalin’s era, protest art was punished by death. In the late 1950s and early 60s, Kruschev ended the terror but his successor Brezhnev who led Russia from 1964 to 1982 oversaw a great period of stagnation; little terror, but equally little progress or liberalisation. Erofeev describes how information about what was happening in the art world outside seeped in slowly and with inevitable gaps and distortions. Artists increasingly lived double lives; patriotically executing soviet realist commissions by day, closet nonconformist modernists by night. But this dual existence brought a crisis of artistic development and dissatisfaction with both the official and the unofficial worlds. As Melamid put it “(we) made a discovery that there was no more god of art and there was no one to worship. The art of nonconformism turned out to be the same rubbish as Socialist Realism. The latter at least had some propaganda uses, but nonconformism was nothing, slippery foolishness, intelligentsia doleful dumps”.

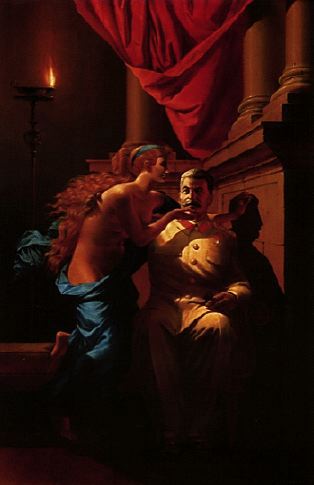

Sots Art could take many different forms. This looks back to the world of socialist realism almost with fondness, anticipating ‘post-Soviet nostalgia’.

Sots (an acronym of Soviet official culture) Art was their response. It was the subversion not of consumer imagery in the first instance, but of official imagery but with the same intent as the Pop Art originators; subversion through parody and irony. And of course, as Soviet society opened up and consumerism started to play a key role, the Sots artists extended their subversion to consumer culture and art as well.

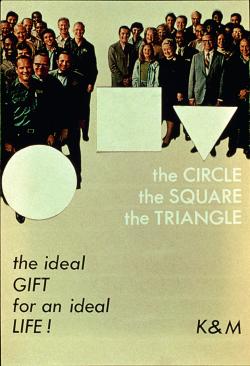

This wonderful piece serves to demonstrate better than any words the absence of any common value system for a shared interpretation of C20 art.

This poster and supporting installation was one of the most appealing things in the exhibition. Subverting geometric abstraction we are assured that “substantiated ideal concepts of pure and clear reason are simple white figures – a circle, a square, a triangle – figures that are from now on destined to become part of your life”.

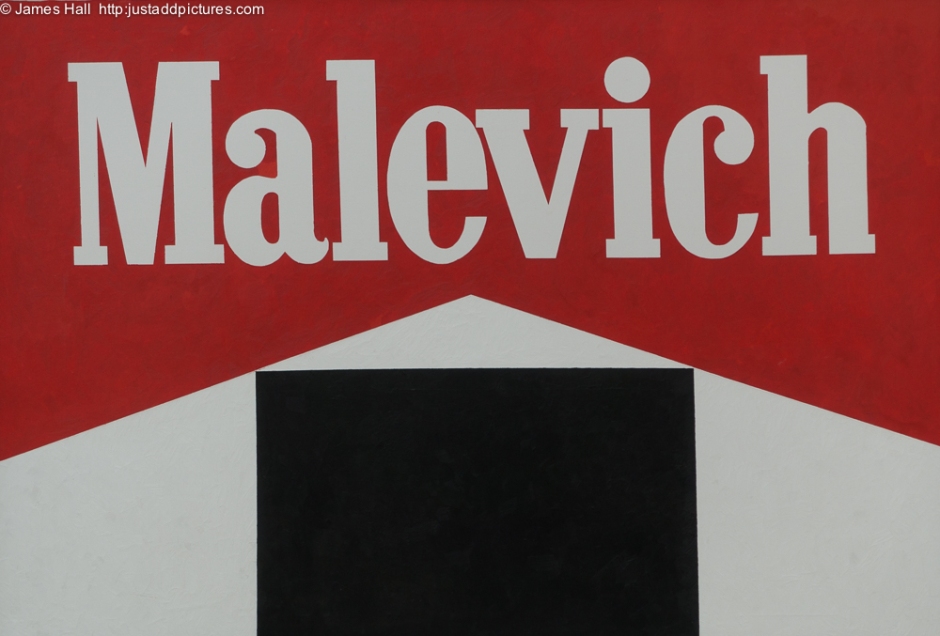

Of course, the founding father of Geometric Abstraction, Kasimir Malevich, could not avoid his own subversion in the creation of Sots Art. He appears several times in the exhibition. This was the most arresting. The Adventures of the Black Square continue.