At the start of 1932 Pablo Picasso had recently turned 50. He was at the pinnacle of his career, acknowledged with his friend and rival Matisse to be the most important painters in France and hence the world. Despite the Great Depression collectors were paying record prices for his pictures. He was financially secure and had both an apartment in Paris and a chateau in the Normandy countryside. His wife, Olga, had created a comfortable haut-bourgeois lifestyle for him and his family.

But all was not well. Detractors were beginning to suggest that he was no longer contemporary and, following the success of a similar show for Matisse, he had committed to a major retrospective of his work in Paris. The professional gauntlet had been thrown down and accepted. He was in the midst of a secret affair with a woman, Marie-Therese Walter, less than half his age and forced to live the two parallel lives that such an affair must entail. And he clearly chaffed under the constraints of his bourgeois lifestyle and his supposed monogamy, such a long way from his life in Montmartre when he first came to Paris thirty years earlier.

In short, Picasso was struggling with a mid-life crisis. He had even purchased the expensive motor car that is deemed to exemplify the male mid-life crisis. In his case it was a large Hispano-Suiza complete with chauffeur. But his mid-life crisis was the stimulant for a year of extraordinary and prolific creativity that is the focus of this exhibition and which helped ensure Picasso’s reputation as probably the greatest artist of the C20.

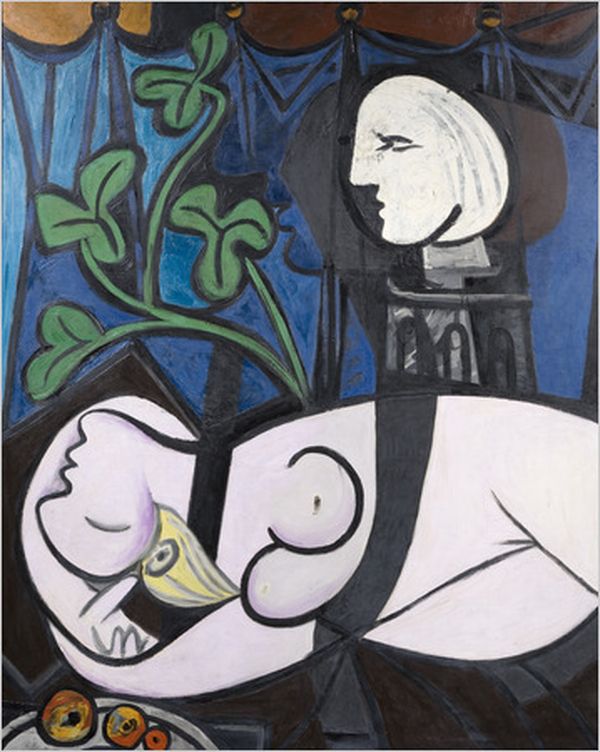

The exhibition comes to the Tate from Paris where it was subtitled ‘L’année erotique’. Certainly the female nude is the dominant form in the exhibition, with the images clearly inspired by his lover Marie-Therese. Inspired by but not drawn from because Picasso did not typically paint or draw from life but from his memory and imagination. These are not pictures of Marie-Therese. They are insights into the mind of Pablo Picasso, where Marie-Therese loomed large. They are large images, created at extraordinary speed, sometimes in a single extended burst of energy, bursting with colour and giving new energy and relevance to traditional subjects. Picasso may have been creating a new language of painting, creating pictures which were highly original, but he was rooted in art history in his choice of subject; the female nude, the still life and the narrative pictures.

The exhibition essentially breaks Picasso’s year into three components. The first half of the year is infused with the energy of preparing for his retrospective at the Galeries George Petit in the centre of Paris and of celebrating his relationship with his lover. The pictures from this period are colourful, bursting with energy and life, and revelling in sexual enjoyment.

The central component is his retrospective itself where a room at the is rehung with some of the key pictures that featured in the show including pictures of his wife and son together with more recent pictures inspired by Marie-Therese.

The third and final component of the show reflects the latter part of the year after Marie-Therese comes close to death and needs to be rescued after swimming in the highly polluted River Marne. This near tragedy is marked by a series of images, drained of the bright colours of earlier that year, representing the rescue of Marie-Therese from the river.

Taken as a whole the exhibition is a testament to a period of enormous creativity, which delivered to the world some of the key paintings of that period. It reinforces Picasso’s artistic genius but reminds us yet again that great artists are very often not good people. There are edges to the images of women that Picasso creates that are more than a little uncomfortable. The exhibition starts with ‘Woman with Dagger’ in which a distorted female figure thrusts a dagger through another figure (her sexual rival? the artist?), and finishes with drawings which merge the rescue of Marie-Therese from the river with rape and sexual violence. And at the centre of the exhibition, and indeed featuring on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, is The Dream in which the female subject’s (Marie-Therese) face springs a large erect penis. Picasso was long concerned with the intersection of sex and violence, and a sense that he was doomed to make women suffer. As indeed, he did.

Overall though it is an important show that reminds us just why Picasso was one of the great figures of C20 art. And if it reminds too that great artists can also be flawed characters that is perhaps a timely reminder that some of today’s flawed characters might be recognised with time to have also been great artists.